How to over engineer a sound classifier

🏡 Hack day idea

I recently moved our washing machine out to the garage, which meant that I couldn’t hear it beep when it was finished. I would have some “false positive” trips out there (through the drizzly British rain!) when timers went off, only to find that the thing was still going. How horrendous.

It had also been a while since I wrote some code just for the sake of building something and I had never done anything with software and sound (recording, cleaning, classification). So, solving this first world problem for myself became my small 💡 idea for a hack project I could work on as the world slowly started locking itself down.

This post is an overview of what I built. It does not cover the day that I spent dusting off the old laptop and generally waiting for all of the updates to download (goodbye, Python 2.7!). It also does not give appropriate credit to the infinite StackOverflow posts that I read along the way.

All of the code for this is on Github in my sound-detection repo.

🎧 Collecting training data

The first thing I needed was some data: I used the PyAudio library for this.

PyAudio is a library that allows you to record audio by reading from a stream, in a similar way that you would read from a file. There was a bit of faff with figuring out sampling and frame rates - I ended up using default values that I found on different examples.

I ended up with the function below that I used to record 3-second long samples of audio. The function returns as a list of arrays - in case you’re wondering, here’s a post about the difference.

Critically, I also added a counter that would tell me (approximately) what percentage of the sample was “silent.” All I did was check what the max value of each array was; if it was less than a totally arbitrary value of 300, I counted it as silent. I tested this by recording a few samples and shouting at my computer.

def record_sample(stream, rate, seconds=NUM_SECONDS):

frames = []

count_silent = 0

for i in range(int(rate / NUM_FRAMES * NUM_SECONDS)):

sound_data = array('h', stream.read(NUM_FRAMES, exception_on_overflow=False))

if max(sound_data) < SOUND_THRESHOLD:

count_silent += 1

frames.append(sound_data)

percent_silent = float(count_silent / len(frames))

logger.info(f"ℹ️ Finished recording {seconds} seconds: {(percent_silent * 100):.2f}% silent.")

return frames, percent_silent

I saved any 3-second sample that wasn’t silent as a wav file, using the wave library. Somehow, I recall seeing some error when I tried to write this function using a with statement, so I ended up opening and closing the file directly:

def save_sample(frames, rate, sample_size):

file_path = os.path.join(

"data",

"live",

f"Sound-{str(datetime.now())}.wav"

)

logger.info(f"⤵️ Storing audio to: {file_path}...")

wf = wave.open(file_path, "wb")

wf.setnchannels(NUM_CHANNELS)

wf.setsampwidth(sample_size)

wf.setframerate(rate)

wf.writeframes(b''.join(frames))

wf.close()

return file_path

With this minimal setup, I did a couple rounds of laundry and ended up with a bunch of wav files! That was the end of day 1 of the hack project.

🏷 Labels

For day 2, I started by having to label the data I had previously recorded. I did this manually, by listening to all of the recordings – well, at least the first second of each one. Luckily, these washing machines don’t tend to beep or spin at random, so all I had to do was find when it started and stopped doing one of those things, and bulk move all of those files into a directory. At this point I was thinking of making a classifier that could tell me about different things that the machine was doing, so I created four groups: beeps, spinning, washing, and “human” (which was usually me coming in and out of the room).

I’m used to regularly labelling text for our classifiers at work, but usually do things like listen to music while doing this. Stepping through and listening to audio files needs your eyes, ears, and hands - this was all encompassing. It is also a prime way to annoy other people in your household.

In summary: this was super boring, so I had a gin & tonic while I was doing this. I ended up with 43 samples of beeps, 588 samples of the machine making noises as part of the wash cycle, 38 samples that were sounds from me, and 748 samples of the machine spinning. I would later come back to this and change it to two classes: beeping and not beeping - which is what I ended up using.

Once that data was sorted into different directories, I loaded up the file paths (and corresponding label/directory) into a Pandas data frame and then used scikit learn for what it is best known for: train test split.

🤖 1D Convolution

Okay, finally! Time for some machine learning. I fired up my browser to figure out how to even begin on this.

This is the bit of the hack that is intentionally over-engineered. I am very aware that all I really wanted to do was detect a high-pitched sound among mostly background noise, and so could have gone down the audio analysis route. But that’s not fun, so I didn’t do that.

At work, we primarily use PyTorch, and so that was my first port of call. I found this tutorial which points to a paper called “Very Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Raw Waveforms” (here’s the PDF). I skimmed the paper - it looks like it’s based on some dataset of urban sounds called UrbanSound8k, which has 10 classes of sounds like horns, children playing, and dogs barking. The tutorial also links to this Colab notebook.

I first tried swapping my dataset into this notebook, but soon hit all sorts of errors. I think this boils down the fact that the tutorial was written for PyTorch 1.1.0, and I was running 1.4.0. Everything was broken.

I ended up going back to first principles. By that, I mean that it had been so long since I had worked at this level of detail in PyTorch that my first few attempts didn’t work at all, and I had to go and re-learn about 1-D convolutional layers. Here’s a really good YouTube video that helped me.

In the end, I made a neural net with a dimensionality reduction step (1-D convolution, batch norm, and max pool), and then a classifier (linear and softmax):

class BeepNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(BeepNet, self).__init__()

self.main = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv1d(

in_channels=NUM_CHANNELS,

out_channels=2,

kernel_size=KERNEL_SIZE,

stride=STRIDE

),

nn.BatchNorm1d(num_features=NUM_CHANNELS),

nn.MaxPool1d(kernel_size=2),

)

self.classifier = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(in_features=298, out_features=NUM_LABELS),

nn.Softmax(dim=1)

)

def forward(self, x):

batch_size = x.size(0)

hidden = self.main(x)

return self.classifier(hidden.view(batch_size, -1))

Once this seemed to be working, I looked into using a GPU to train the model. I spent a while moving the data into Google Drive and reading about how I could load it all into a Colab notebook. In the end, this was another unnecessary rabbit hole and I trained the whole thing in minutes on my laptop.

I trained the model for a few epochs and it converged pretty fast. I then looked at the examples of what it was doing, and the results seemed legit. I hear you asking - what did you do about overfitting? The answer is that I did absolutely nothing. A model that was overfit on these beeps (that all sound exactly the same) was fine.

You can see the notebook that I used here.

⏭ Deploying to production

The final stage was to make something that could use this model to detect the beeps, and somehow let me know.

At this stage, I had two different components: a PyAudio thing that would record samples and save them to a wav file, and a PyTorch model that would use torchaudio to load data from a file and give it to the model. Instead of figuring out a way for the PyAudio data to go directly to the model, I decided to keep what I already had and use the disk as an intermediary.

Here’s how I made this unnecessarily complicated: I decided that it would be unacceptably slow if all of this happened in a single process. So I turned back to an old friend, the multiprocessing library - and found out how multiprocessing has a neat bug where Python crashes on macOS; setting some weird flag export OBJC_DISABLE_INITIALIZE_FORK_SAFETY=YES before running it fixed this 🤷♂️.

The main process in my pipeline records a sample of audio and (if it is not silent) saves it to a file; it then pops the path to the file onto a queue. On the other side, a classifier process reads from that queue and loads up and classifies any file that is popped onto it.

What does it do if it detects a beep? I hunted around for different options here. One of the first options I thought of was to send myself an email; the problem is that I’ve turned off gmail notifications (and my life has been much better since). I then went down a rabbit hole of options - Signal, WhatsApp, SMS gateways, paid services, and all of that.

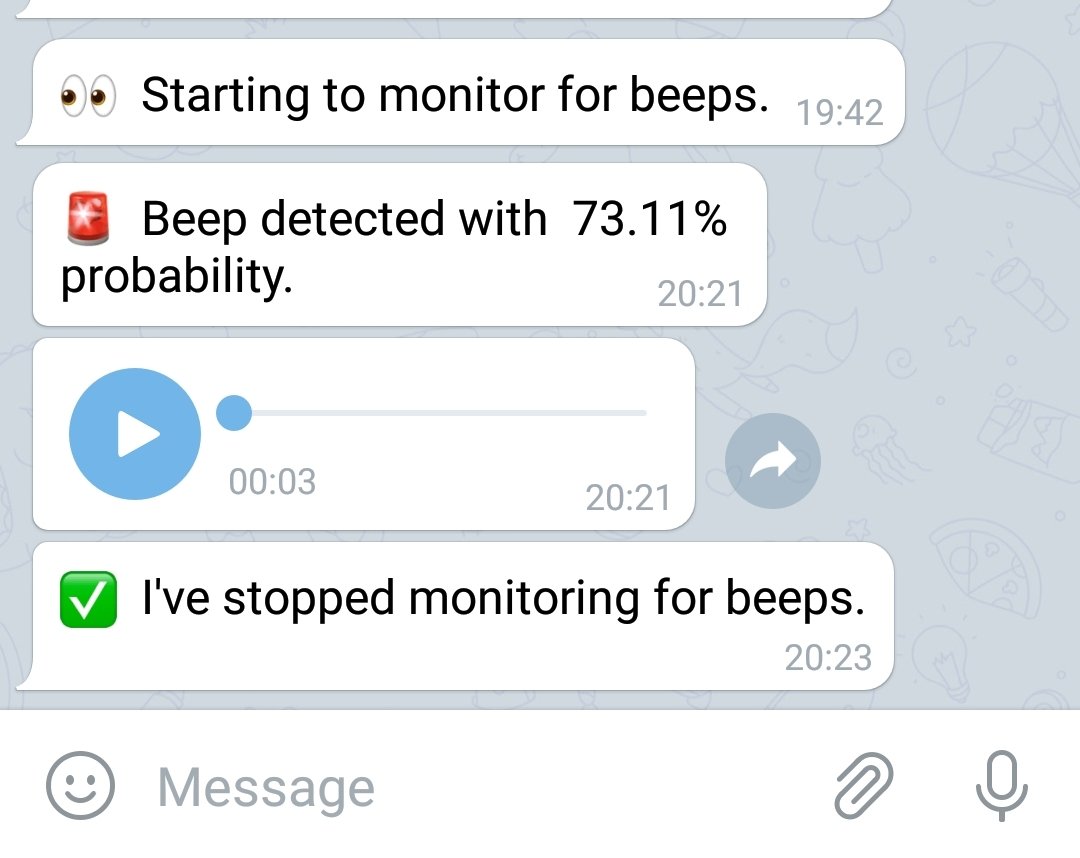

I settled on using Telegram, because I stumbled onto a Medium post about setting up a bot and sending it a message with Python, and it looked do-able. But, what if the model was wrong? How could I avoid that short walk out to check? I decided that the pipeline should also send me the actual audio that it thought was a beep. Sending a snippet of audio via telegram was not something that looked super straightforward, until I ran into the Python Telegram Bot library. The main problem I ran into was that this library would only send sound files that were formatted as mp3s. Instead of re-writing everything to always use mp3s, I found an mp3 encoder called lame that could be installed via brew. I found that before finding any Python library that I could use directly, so I just called this function from Python:

def convert_to_mp3(file_path):

path_fields = os.path.split(file_path)

file_name = path_fields[1].replace(".wav", ".mp3")

result_file = os.path.join(path_fields[0], file_name)

logger.info(f"🎧 Converting: {file_path} -> {result_file}")

command = f"lame --preset standard \"{file_path}\" \"{result_file}\""

result = os.system(command)

logger.info(f"🎧 Converted to mp3 with result={result}")

return result_file

🎉 That’s it! …Or was it?

All of this means that I now take my super old laptop and fire up the pipeline after I’ve started the machine. I then go and hang out, anxiously waiting for a message. Here’s how I tweeted when it started working!

The first time it worked, I was overloaded with messages. I had forgotten to add a way for it to not send me a message every time it detected a beep (which was happening in multiple 3-second interval successions), so I had to add in a way for it to be rate-limited to one message every X minutes.

There were also a couple of times that it didn’t seem to work: the classifier process would die, the laptop’s wifi would have briefly gone down, or other such oddities. So I added in a bunch of logging, a time out (it would message me if it hadn’t detected a beep in more than X minutes), and I added in the tenacity library’s annotations so that it would retry message sending.

💻 What’s next?

All of the code for this is on Github in my sound-detection repo. Feel free to use it, find bugs, and tell me what’s wrong with it.

The silliest thing about all of this is that I now have to fire up my old laptop when I want it to monitor a laundry cycle. Some day in the future I’ll think about spending some time getting this to work on a Raspberry Pi or some other device that I can leave out there.