Audit Bot: a prototype for automated AI audits

At the tail end of a sabbatical last year, I participated in the AI Audit Challenge that was run by Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. To my great surprise, I won the award for greatest potential! 😲

This post has reflections about my previous experience with being involved in model audits, what inspired me to build something, and a rundown of what I built–echoing the slides I presented in the online session at the end of June.

🏦 Audits and banking

While the idea of auditing AI may still be in its infancy, auditing decisioning systems in banks is not. I’m no expert on the topic, but have sat on both sides of the table here in the last few years: either models that were trained by my team were being audited, or I stepped in to help with audits of models that were trained by others.

Banks have the concept of managing risk baked into their organisational structure. Staff will sit in different teams, that are organised into three lines. Each line has different reporting structures, in a way that endeavours to create the right processes to manage the risks and responsibilities of dealing with many peoples’ money. Very broadly, these three lines of defense breaks down as follows: the first line is building controls and owns risks associated with it, the second line reviews it, helping to identify new or unmitigated risks, and the third line conducts independent audits encompassing all of the work between the first and second line. In the case of AI, it might not be uncommon to hear that a model needed to go through second line review before deployed.

🔍 Auditing AI

One mental model that I found useful when being involved in audits is that of defensibility. Training a model requires a spectrum of important decisions to be made, ranging from data selection, the model type, the training & evaluation process, setting thresholds, through to deploying it and monitoring the outcomes it achieves. The crux of many discussions boiled down to being able to justify–and, where necessary, provide evidence that justifies–the decisions that were being made along the way. Risks will never be fully vanquished, but people should be able to demonstrate that they are known and within appetite.

To take a relatively simple example: a binary classification model may have been trained on a dataset with a given distribution of positive and negative labels. Perhaps that data was pruned according to some criteria. The types of questions that could surface include: does that distribution still hold, today? Are those exclusion criteria justifiable? And so on. From that point of view, this is not too dissimilar to the rigour that you might expect in academic research.

Overall, 5+ years in a bank has shifted my views on audits and regulation–which usually attracts a fairly negative response in the tech world. When done well, I’ve seen it lead to much better outcomes: better systems, built to a higher standard, with stronger controls and quantitative evidence of what they achieve. However, the process is far from perfect: the audits that I’ve been involved in have been very laborious. They require a lot of analysis, discussion, and question-answering, and their primary focus ultimately centres on a written document1, rather than the code or models themselves. Machine learning audits, in particular, were also often complicated by an imbalance in expertise: the people being audited may have more expertise in machine learning than people conducting the audit. At best, that has meant that audits have had to be accompanies by a lot of education. At worst, auditors will evaluate models in ways that make absolutely no sense.

💡 What if the model isn’t yours?

All of the audits that I’m reminiscing on above had common foundations: auditing a model that was (a) trained for a specific purpose, and (b) controlled, end-to-end, by the organisation that wanted to deploy it to fulfil a specific purpose.

These two assumptions are no longer true in the era of foundation models and machine learning as a service. We’re left in ambiguous territory, where accessing models via APIs:

- ✅ is faster to get up and running and deliver value;

- ✅ is probably better, particularly for well-established problems2;

- ✅ opens up people’s time to work on company-specific problems

- ❌ it cannot be evaluated in the traditional ways;

- ❌ means it could be changed3 at any time, without us knowing;

The latter two points are where I started with for Stanford’s AI audit challenge.

🤖 Audit Bot

For my challenge submission, I married two ideas together:

1️⃣ Model Cards are a popular approach for capturing a snapshot of a model’s performance in model hubs like Hugging Face. They usual describe the model, its intended use and limitations, and information about the model development–experiments, datasets, evaluations. They’re akin to an abbreviated version of the documents that teams produce for model audits. But they are manually written–this means that they’ll only be updated if someone decides to update them.

2️⃣ System status pages are websites that are widely used across the tech world to show the uptime status of APIs; they appear all the way from backend engineering tutorials through to products like incident.io’s one; even Open AI has a status page. Their primary function is to show when systems are unhealthy or down, and to enable interested folks in subscribing to updates. However, they’re never used to track the performance of the ML model that sits behind an API, just its availability.

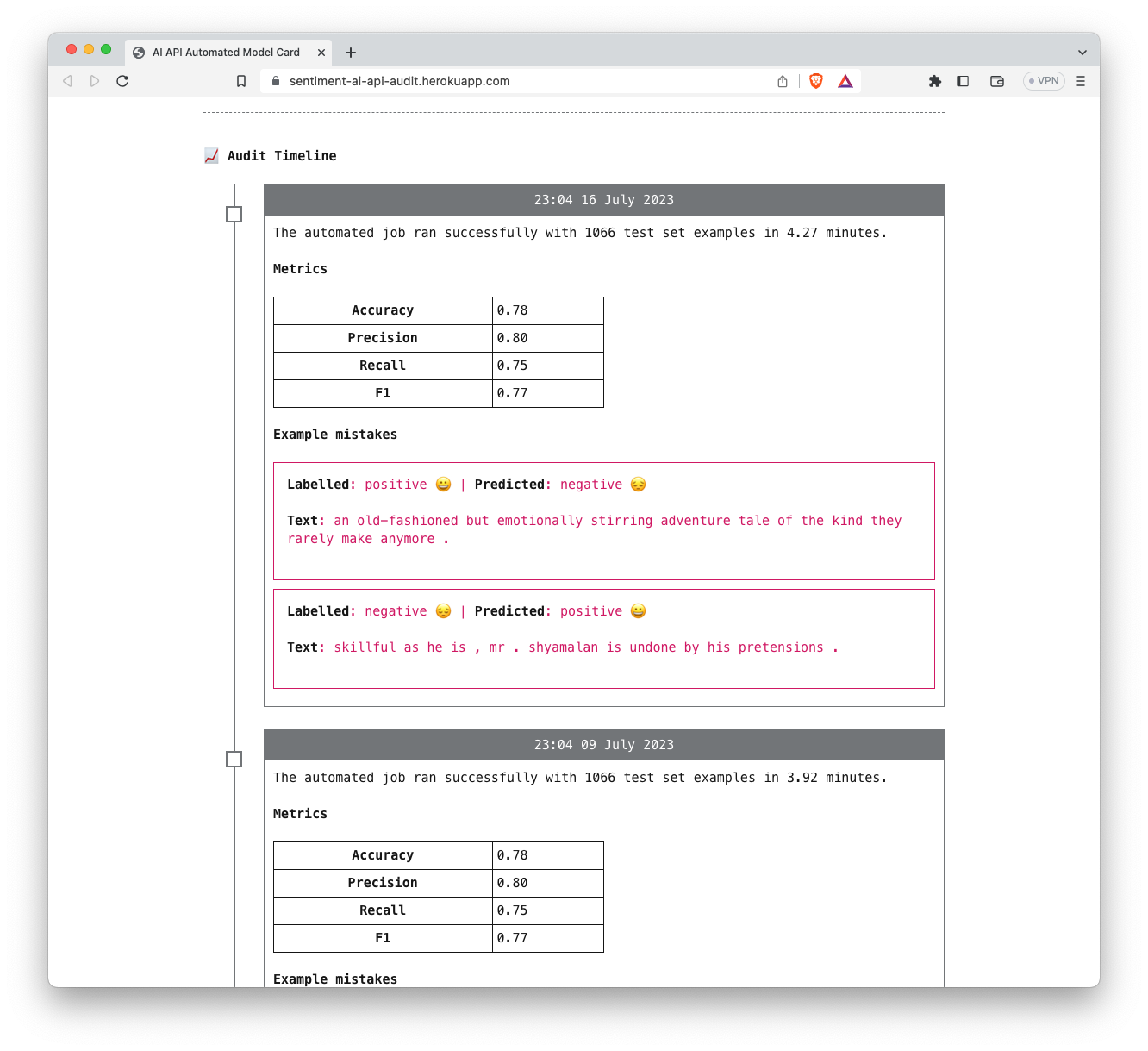

Putting those two ideas together, I built and open sourced a cron job that polls the Google Sentiment detection API with all of the test set entries of an open dataset once a week, and then publishes its results in a timeline on a website, which has also been open sourced, and was deployed on heroku:

The idea was that this sort of mechanism could be used to automatically identify regressions in a model’s performance and bring transparency to when it improves. Over the course of several months, I monitored the Google sentiment detection API. Unfortunately, nothing spectacularly interesting seemed to happen in this time 😅–but I didn’t go too deep into the data.

🔮 Looking forward

Audit Bot was just a proof of concept and a prototype. I’m probably going to take the website down soon so that I have one less thing to think about.

Taking this beyond the initial idea would require extending it to many different types of APIs, and thinking more about how this could be used and abused in practice. After all, it’s easy to game: the models behind those APIs may be trained with those same open datasets, or could easily be amended to know when they are being queried with entries from one.

🔢 Footnotes

1: There are some audit documents that I’ve read for a single (and, arguably, “simple”) model that are longer than my PhD dissertation.

2: Things like sentiment detection in text, object detection in images, etc. I’ve rarely seen a time when a custom sentiment classifier does better than a (perhaps fine-tuned) generic one.

3: This could be either intentional (the company shipping a new model that is intended to be better) or unintentional. Recently this recent paper claimed that GPT-3.5 and 4 got worse over time, but that may have been a measurement bug.