"Just get some labelled data"

Labelled data underpins all of supervised learning: our ability to wrangle data into some representation of “input” and expected “output” is what enables us to train models that can do so many different and interesting things.

In a lot of research and machine learning competitions, a labelled dataset is provided–so we’re often not geared to think about how those labels (or that dataset) came to be. Outside of that context–inside of companies–it’s usually up to the Machine Learning person to define the labels they need to solve a problem.

Creating, inferring, or designing the labels that we can use to train a model can be an extremely nuanced exercise–even before we get to thinking about “advanced” things like label drift. So why might this exercise be complex, in practice?

This post runs through a variety of cases that I’ve come across over the last few years. It’s not meant to be exhaustive; this is just a small ode to the folks who spend countless hours on the toil that is “just” getting some labelled data.

💡 The “ideal” case

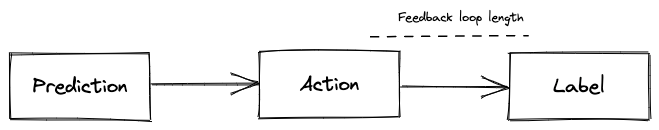

In the simplest case, a system makes a prediction; based on the prediction, an action is taken; the result of the action is a label. Each of those steps is logged.

A canonical example here is: a classifier predicts that an email is likely spam (prediction), the email is moved into the spam folder (action), and then the customer selects the email and clicks “not spam” (label)1.

In this case, it should be easy to attribute a label back to a prediction. You just need to understand how long you need to wait to be able to do that: the time between the action and the label may vary depending on the application. There are cases where labels are generated quickly (for the most part, systems that rely on things like clicks, conversions and user interactions in a session) or slowly (when predicting long-term outcomes like ‘churn in the next 30 days’).

However, in a huge variety of cases, labels are generated over a variable amount of time. They trickle in, as people intermittently check their spam folder. So you need to have ‘reasonable’ guardrails in place: just because an email was moved into spam yesterday and not moved out does not mean that the prediction is ready to be filed as a true positive2.

Even the simplest case has some gotchas! So how do things get weirder?

🔀 Funnels are everywhere

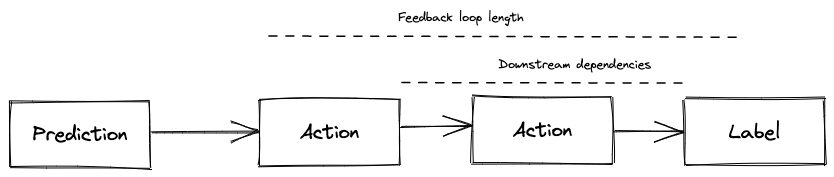

Data labelling becomes more complex when predictions are separated from labels by several steps. There may be more decisions that happen between the system that makes the prediction and the outcome we want to predict:

In an e-commerce (purchase prediction) setting, there may be a few screens a customer has to navigate between, from getting a recommendation through to basket/check out and actually purchasing an item (label). There may be more than one sequence of screens that customers could navigate between these two. In a customer support setting (topic classification), the customer case may be transferred manually and assessed by different humans from their original query through to the conversation being tagged with a topic (label).

In all funnels, abandonment abounds, and attribution becomes much harder. The amount of information available may change as you go down the funnel - from a customer just saying “hello” in a chat screen through to their case being tagged with a topic when it is closed. There may be competing systems (or, worse, competing teams!) - maybe the search results system is getting cannibalised by a checkout screen upsell system. In all of these cases, it’s almost impossible to reason about “labels” without a deep knowledge of the product or underlying processes.

❌ A lot of data is never labelled

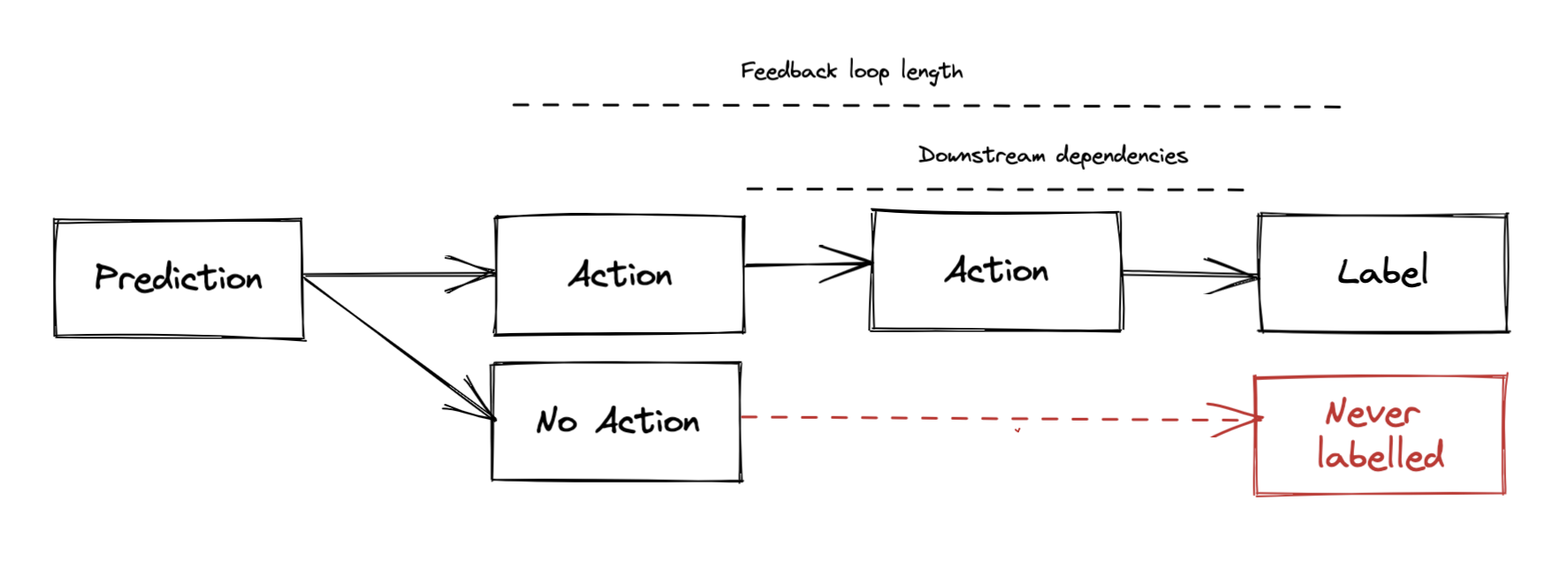

Any system that is making predictions that regulates access to the rest of the system will never know whether it was right or wrong for a set of cases.

For example, social networks may use models to predict whether a new signup is a bot or not: if the system predicts a new signup to be high risk, the sign up can be blocked. But then, the system has no way of observing whether the decision it made was correct.

These systems are full of boggling counterfactuals. What if we had signed up that applicant? These systems can be very difficult to experiment with, particularly when you would like to expand its capabilities (e.g. sign up more customers). One of the strategies I’ve seen here is thinking about enabling systems to act on a small percentage of predictions that are close (just below) the decision boundary, as a way to get some data for populations that would otherwise remain invisible.

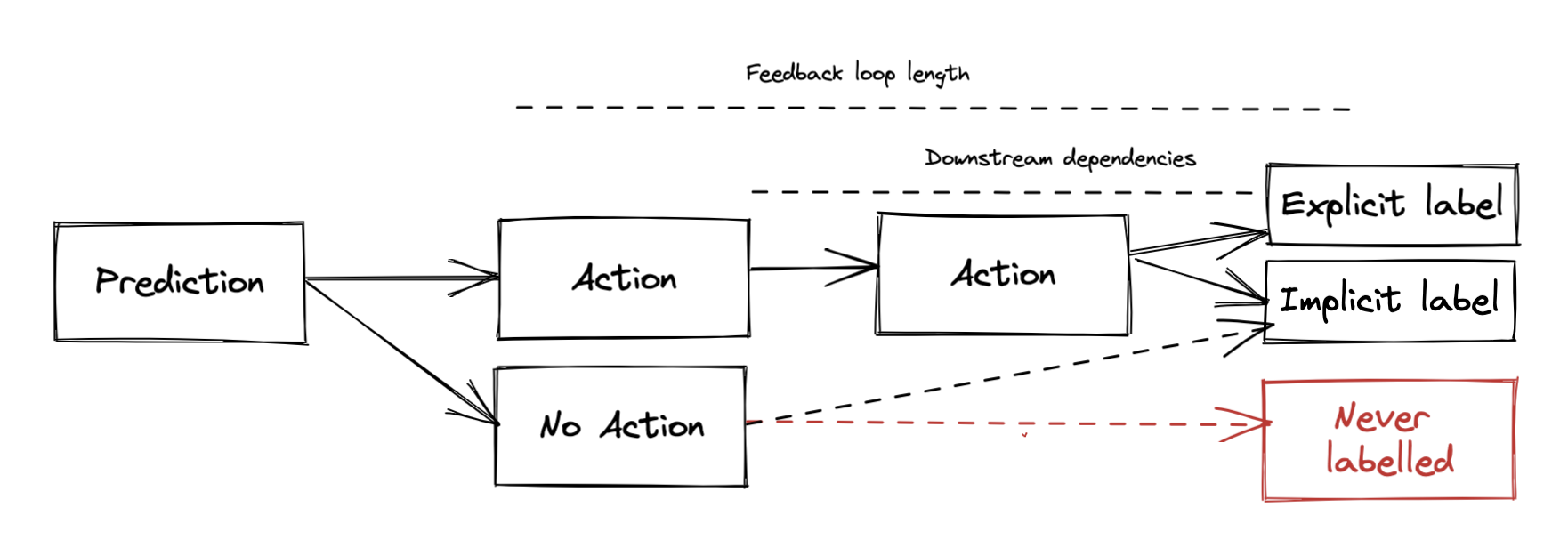

🤔 Some labels are implicit

In many cases, labels are derived from explicit actions: a customer support agent tagging the topic of a conversation, the email user selecting an email and clicking “not spam,” and so on. But there are many cases where labels can be derived from implicit actions too.

Explicit labels usually come from something that happened (like a doctor labelling an x-ray). Implicit labels are often inferred by observing some events and making assumptions about what that means (a person listening to a song repeatedly might mean that the person likes the song?)3.

There is no hard-and-fast rule about how to work with implicit labels. Search engines are a good example here: if a customer searches for X and then clicks on a link, that could be a good signal (or label) that they found what they’re looking for. But it might not be, if they come back and search again. And if they searched for “current time in London” and were presented with an answer, then not clicking anything at all might be a signal that they found what they needed.

🏷 Some labels are not deterministic

Data labelling as a service is fairly popular. The idea is that you can submit a bunch of “things” that need to be labelled to this service and they do the work to label everything for you. These services work for a subset of problems where we would benefit from labelled data: anything where the system learns from implicit customer behaviour (clicks), or anything where the label is subjective to the customer (preferences) are not suitable for data labelling services.

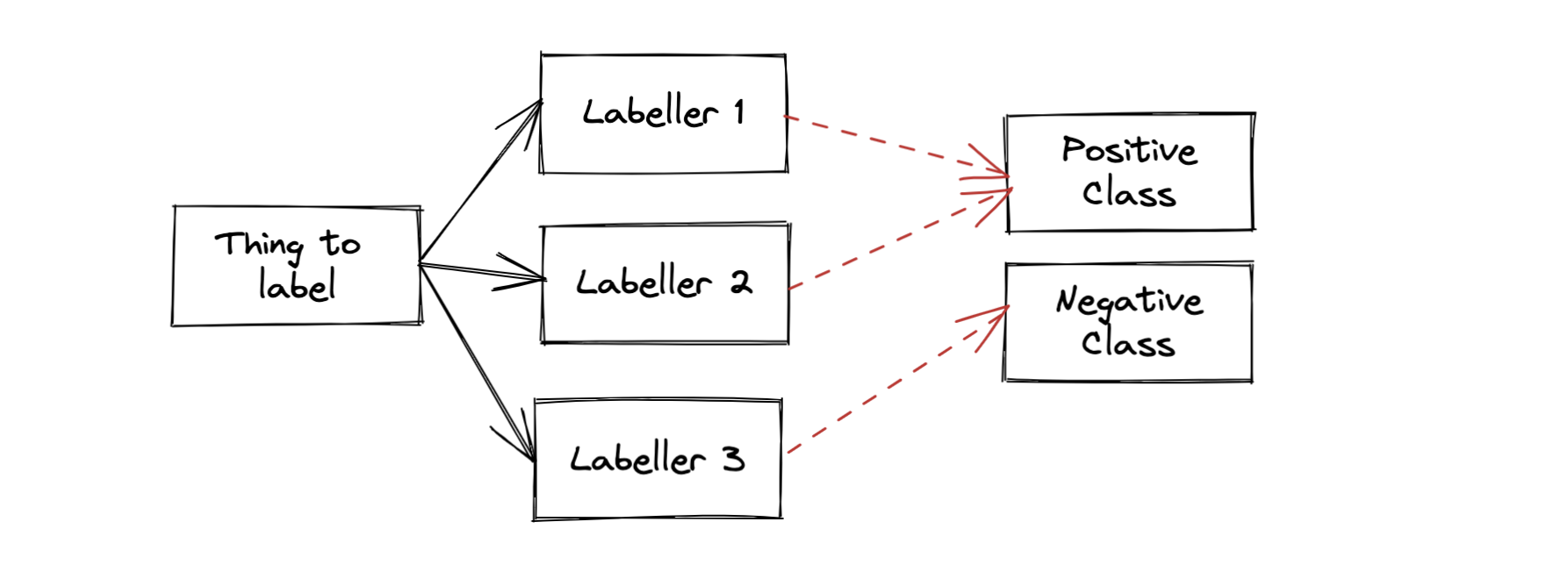

But, even for those problems that do suit data labelling–if you ask three people to label the same thing, they don’t always agree:

I’m reminded of a time where my team was manually labelling some text data. There were a few times that we would disagree with each other or (worse) would not have enough information from the input to make a decision. For the former problem, you need a way to get to a sense of consensus (maybe a majority vote?) and see what impact this has on your model.

🤯 Labels might come from a different place

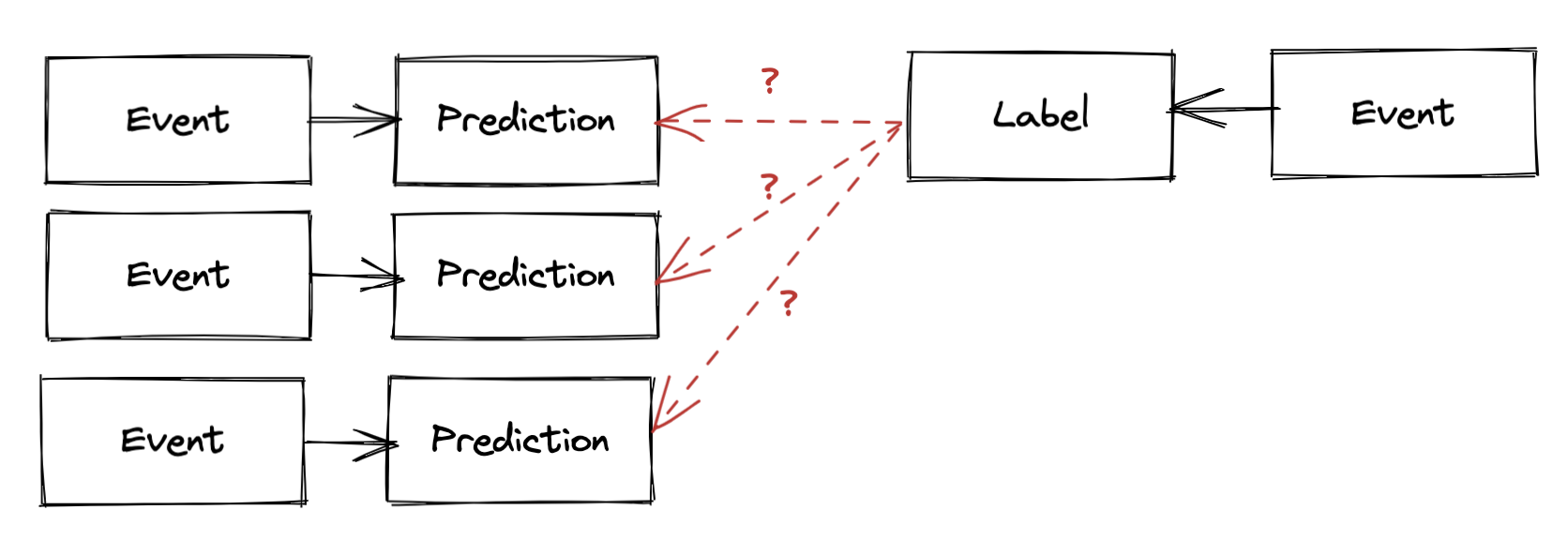

The examples above have charts that flow from left to right: they are sequences of actions that can–within their complexity–be wrangled into some kind of representation of a “label” using a 1:1 mapping between things that happen.

The final shape of problem I’ve encountered is when the source and granularity of the labels does not match that of the input at all:

For example, imagine training a model that needs to make a prediction every time a transaction is made. But the outcome that you are trying to predict is based on reports that were generated by investigating the user who was making all of those transactions. How do you put these two together–mark every transaction from a user with the label for that user? Only those before/after the report was submitted?

⛔️ I’ll stop there

Building a labelled dataset is an art. It encodes so many decisions; it requires deep expertise in a product or process and the craft of machine learning. It fundamentally builds up a representation of a problem that unlocks it for automation. And this post didn’t even cover anything related to linking the labelling exercise back to the business outcome we wanted to achieve.

This laborious (and, sometimes, thankless) task is often one that is met with frustration–people yearn to skip ahead to “the machine learning bit.” But, in the end, labelling data is one of the most fundamental parts of the machine learning bit. So, to all of you who have been told to “just” get some labelled data: this post is for you.

🔢 Footnotes

1: I most recently came across a diagram like this in Chip Huyen’s Machine Learning System Design Lecture 10 slides.

2: The most notable part of this is that the time it takes to generate labels is a lower bound on the rate of experimentation that you can do when developing this system: that rate is the minimum amount of time it will take you to know whether the predictions are ‘good,’ and so you won’t be able to move any faster than this. So pick your problems wisely!

3: The explicit/implicit dichotomy was popularised in recommender system research, when the community moved from largely relying on the former (star ratings) to the latter. It’s surprising how often ML problems have interchangeable formulations using either of these types of labels.