Testing SQL the hard way

📊 Context

It’s not uncommon for Data Science workflows to have large chunks of SQL. Maybe you have a sequence of queries that you run every day to produce dashboards, or maybe you have a bunch of queries that spit out features that you feed into machine learning algorithms. If you’re a Data Scientist, you’re bound to have written a SELECT statement at some point of your day!

There’s an online wiki for programming languages called progopedia which lists SQL as “not a programming language:” this perfectly characterises everything that is strange about these words that we write, execute, and rely on to get our insights right every single day. SQL doesn’t have all the sensible things that real programming languages have to help us feel confident that they are doing what we think they’re doing. Primarily, it lacks a straightforward abstraction for “unit” testing.

About a year and half ago, a colleague Jack and I were wrangling with a query that had to be right–we are, after all, working in a regulated industry. We were dealing with a bunch of queries that were orchestrated together with Airflow. The main problem we had was that we could not rely on the input to our query being right and needed to prevent this query from quietly succeeding if anything in its results was wrong.

We went the entire journey from manually validating entries in our table to automating the detection and reporting of inconsistencies so that we could flag or fix errors that were upstream of our query: this post is a heavily simplified example of what we did. In case you’re wondering, I’ve called the post “testing SQL the hard way” because we have now abandoned this approach (and replaced it with dbt). But it had some fun lessons, so here goes!

👯♂️ A table of users

Let’s look at a toy example: let’s say that we want to make a table that has some key information about all of a company’s customers. I’ve written all of the snippets below in BigQuery SQL, so that you can copy/paste it into the console and play around with it yourself.

We start by building up some mock data. Imagine you have a JSON payload (an “event”) each time a user creates an account, with the user_id, the timestamp of when the account was created, and a bunch of other critical fields. Something like this:

WITH account_created_events AS (

SELECT *

FROM UNNEST([

"{\"user_id\": \"user_1\", \"account_created\": \"2020-01-01\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_2\", \"account_created\": \"2020-01-02\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_3\", \"account_created\": \"2020-01-03\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_4\", \"account_created\": \"2020-01-04\"}"

]) AS event

),

When users finish some set of actions, we get another event to tell us that the user has completed their signup. Here’s some more mock data, for those same users:

signup_completed_events AS (

SELECT *

FROM UNNEST([

"{\"user_id\": \"user_1\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-02\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_2\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-03\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_3\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-04\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_4\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-05\"}"

]) AS event

),

We can take those two events and create a table with one row per user:

-- Extract the account creation columns

WITH accounts_created AS (

SELECT

JSON_EXTRACT_SCALAR(event, "$.user_id") AS user_id,

TIMESTAMP(JSON_EXTRACT_SCALAR(event, "$.account_created")) AS account_created

FROM account_created_events

),

-- Extract the signup completion columns

signups_completed AS (

SELECT

JSON_EXTRACT_SCALAR(event, "$.user_id") AS user_id,

TIMESTAMP(JSON_EXTRACT_SCALAR(event, "$.signup_completed")) AS signup_completed

FROM signup_completed_events

)

-- Join them together

SELECT

user_id,

account_created,

signup_completed,

TIMESTAMP_DIFF(signup_completed, account_created, HOUR) AS signup_time

FROM accounts_created

LEFT JOIN signups_completed USING (user_id)

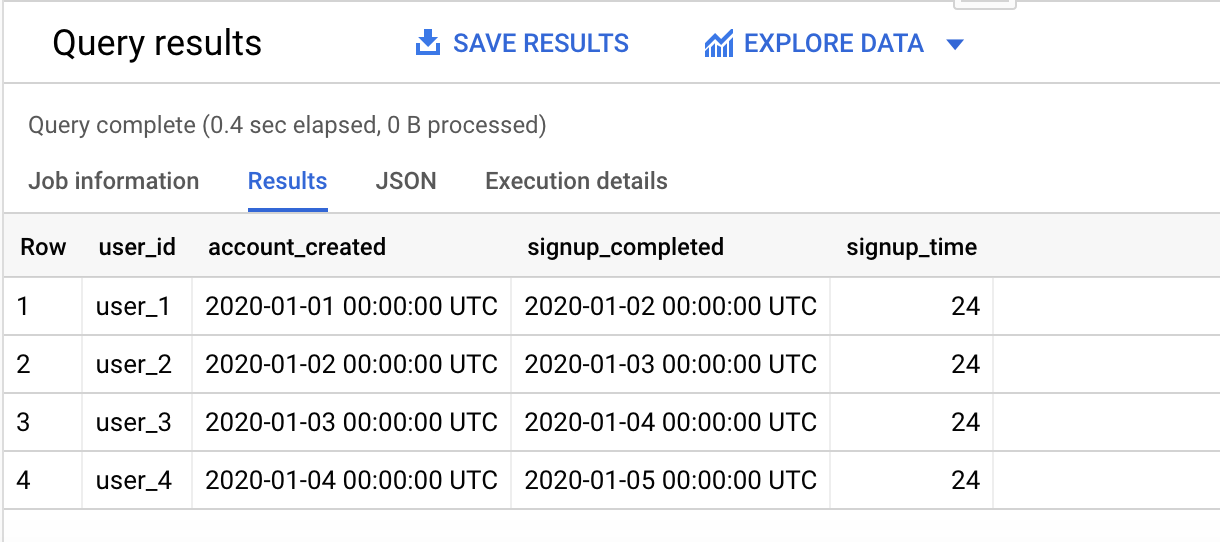

And here are the results:

Perfect! This is the ideal analytics table to answer a ton of different basic analytic questions: How many users do we have? How many of them signed up today? How long does it take users, on average, to complete signup?

This is also the type of table that could be extended with tens (or even hundreds) of columns, each representing unique pieces of information about each user. It is the type of canonical data table that could grow to having tens of contributors and many tens of use cases. As long as this table maintains its core structural assumption (one row per user), we’ll be good to go.

How could this go wrong?

🙃 Someone completes the signup flow twice

Let’s imagine that a customer, due to whatever reason, completes the signup flow twice. Maybe there’s a bug in the app and the customer uninstalls & reinstalls the app, maybe there was a bug or failure in the backend service that is emitting those events (whatever, it doesn’t matter!).

Nothing has changed in the analytics code base, but now we have two signup completed events for that user:

signup_completed_events AS (

SELECT *

FROM UNNEST([

"{\"user_id\": \"user_1\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-02\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_2\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-03\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_3\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-04\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_4\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-01-05\"}",

"{\"user_id\": \"user_3\", \"signup_completed\": \"2020-02-04\"}" -- Yikes!

]) AS event

),

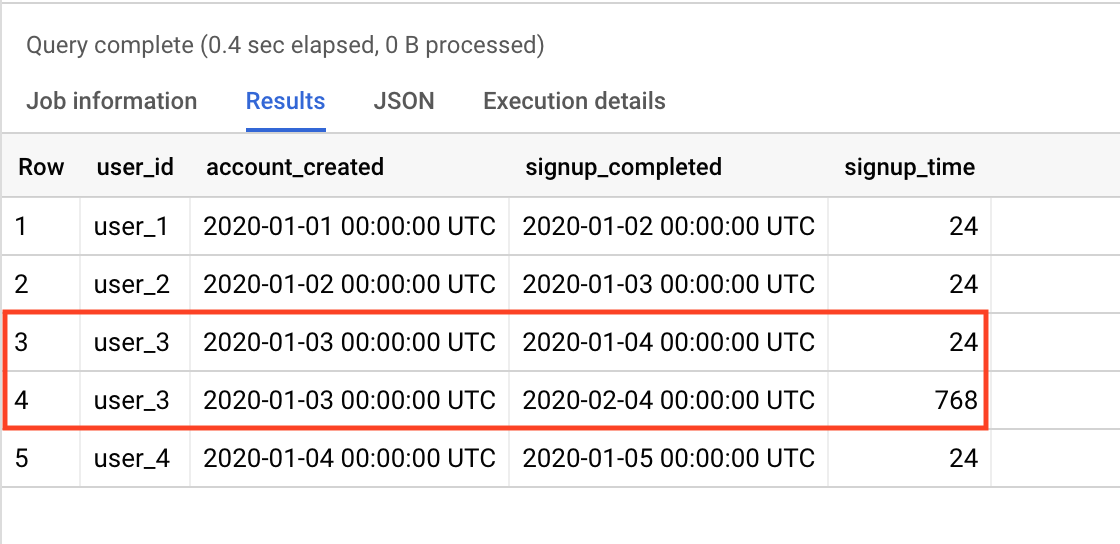

This tiniest of errors – something that is largely invisible to the person who is writing the SQL, breaks the table: user_3 appears twice. Not only that, but your stats on signup completion rates have shot through the roof!

Herein lies the problem: a tiny issue in the data has propagated itself through the LEFT JOINs in the analytics code base, and has completely skewed some metrics that you are using.

Of course, you could argue that this is fairly trivial to fix: we’d need to add in a pre-processing step on the signup completed events to pick the one we care about more, and spit out one signup event per user. But what if this table has tens or hundreds of columns? What if the person contributing a new column is not the person who added the signup stats column, so doesn’t know this? What if we have two of these types of problems manifest at the same time? What if this table is input to some downstream queries, and all they know is that their table is now wrong?

These problems are more of a headache to discover and diagnose than they are to fix. Indeed, they may first manifest as a question about the metrics (“why has our average sign up time gone through the roof?”) and not about the data.

🐛 “Unit” testing a table in two steps

This post is not about fixing those bugs: it is only about an approach that we used to use to detect these types of problems with some sort of meaningful error message. At its core, this method relies on enumerating your assumptions about the structure of the table, and then triggering an error in the query execution if you find any.

In our example, our key assumption was that the table has one row per user.

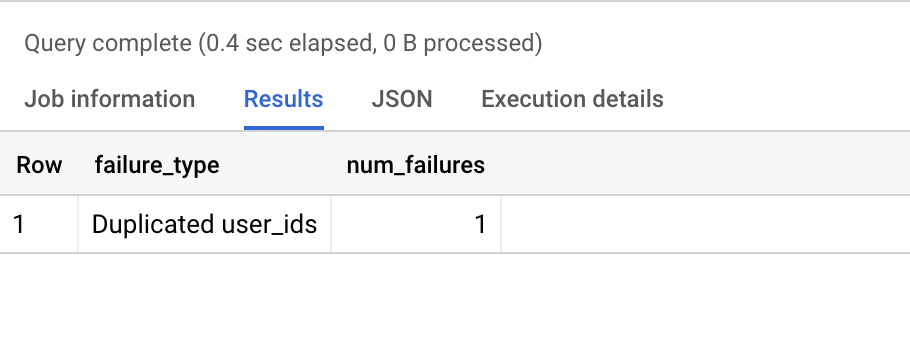

Step 1. Separately from the query above, we wrote a query that should create an empty users_table_errors table if the users table’s assumptions were not broken:

WITH user_validation AS (

SELECT

user_id,

COUNT(*) AS num_rows

FROM users

GROUP BY 1

HAVING num_rows > 1 -- Should never be the case, amirite?

)

SELECT

"Duplicated user_ids" AS failure_type,

COUNT(DISTINCT user_id) AS num_failures

FROM user_validation

-- Union all with any other validations (e.g. validating time stamps)

These types of queries are an extremely useful way of (a) documenting what you expect, and (b) creating a table of all of the (in this case) user ids that don’t match your expectations – and how many times each one is duplicated.

Step 2. Now that we have a way to identify errors, we need a way to stop our query from completing successfully if any errors are found. The first way we did this was to force BigQuery to compute something it couldn’t if it found errors: we would literally encode a one divided by zero. Shortly after, we found a debugging function buried in the BigQuery documentation.

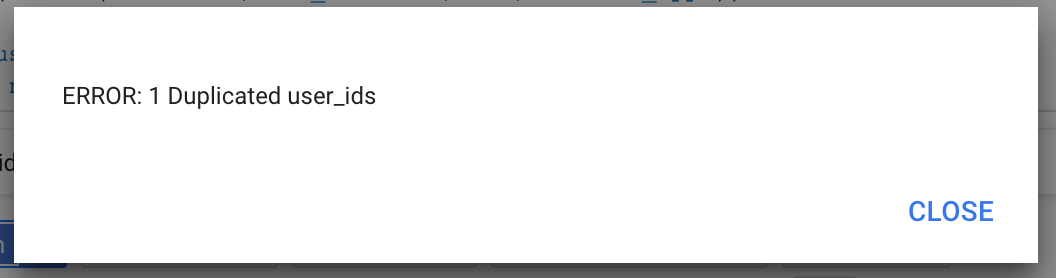

If a validations table is not empty, we used this ERROR() function to stop the query! It looks like this:

SELECT

ERROR(CONCAT("ERROR: ", num_failures, " ", failure_type)) AS error

FROM users_table_errors

WHERE num_failures != 0

If you run this in the BigQuery console, it pops up with this kind of alert:

The final workflow would run (1) the original query, (2) the validation query, and then (3) the error query. This approach really accelerated our ability to diagnose and fix errors; it de-coupled the code SQL that did the work from the SQL that did the validation, and it automatically documented all of our assumptions about a given table.

For our example, above: we’d see an error message that reads ERROR: 1 Duplicated user_ids; we’d pop open the users_table_errors and see that it has 1 entry with user_3; and voilà, we’d already be on track to finding and resolving the problem.

🏚 Why is this the “hard way” of testing?

We got a lot of value out of the approach above; the major trade-off was that we had to write (nearly) double the amount of SQL. This is not too dissimilar from what happens in other programming languages, where we can write unit tests.

However, these are definitely not unit tests: we would primarily discover errors in the data when the analytics pipeline was running, and had to make choices as to whether we wanted our (fairly huge) graph of queries to halt running completely on every error, or continue with warnings. We had started designing ways to quantify the severity of errors (both in terms of columns and in terms of number of affected rows), to run queries on samples of data, and more.

By the end of 2019, though, the Data Science team at Monzo migrated to using data build tool, or dbt. If you want to read about why we think that was a good choice, Stephen’s post here describes things that we like about it. It helped us to automate a lot of the work flow that I’ve described above, and more.

Does this solve everything we need to ensure reliable, consistent, and scalable analytics queries? Absolutely not. The experience of writing this kind of “code” is still very much characterised by the “try running it and see if the results look sensible,” which is a far cry from where it could be. But it’s a great step in the right direction.