Five lessons from building machine learning systems

In January 2017 I left Skyscanner, where I was a Senior Data Scientist. Like I did with a previous post a couple of years ago, I thought I’d summarise my journey by collecting some thoughts and lessons learned from the projects that I was involved in — which all focused on building different machine learning features for the Skyscanner app.

This post does not have any breakthrough insights on specific algorithms or technologies. Instead, I focus on a few broader aspects of data science: definining methodologies, dealing with uncertainty, building pipelines, and fostering a culture of machine learning.

5.

My first squad designed, built, and ran some experiments with a pipeline that uses different kinds of unsupervised ranking in order to compute localised destination recommendations. We set out to build a new system, and so we didn’t know a lot of things: what data should we use? What kind of ranking algorithm? Where will the feature appear for users, and how will they interact with it?

As a data scientist working in a new problem space, there’s certainly an initial urge to reach for the latest algorithm right away. Similarly, as engineers working on a new system, there’s an instinct to automate and scale everything within the problem’s scope. However, that is a far cry from what we needed in order to get the initial system up and running: what we really needed was a foundation that we could use to run experiments.

Our focus shifted towards designing a pipeline that would allow us to run all kinds of experiments: for example, experiments that changed input data type or size, parameters, or switch algorithms —all aimed at demonstrating how much we were incrementally making a difference, rather than proving that we had solved the problem outright. You can read more about the pipeline’s initial architecture here.

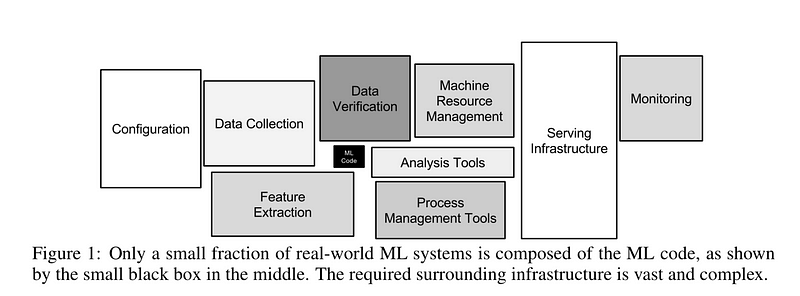

The process itself encompassed many small details and tasks that the data science commmunity does not tend to celebrate (at least, not as much as the newest algorithm!). The algorithm itself was a very small piece of the whole ecosystem — much like the little black box in this image:

When I presented this work in the industry session at the ACM Recommender Systems conference (the abstract pdf is here), I recall feeling a form of impostor syndrome — from an algorithmic perspective, this system is very simple compared to the typical academic papers that are presented at the conference. However, it works! You can see this feature today in the iOS app if you navigate to the ‘explore’ tab, where there are various groups of destinations.

Lesson: Getting a data pipeline into production for the first time entails dealing with many different moving parts —in these cases, spend more time thinking about the pipeline itself, and how it will enable experimentation, and less about its first algorithm.

4.

A squad that I spent many recent months working with focuses on improving the search experience in the app. As part of this, we ran experiments that aimed to explore how learning to rank flight itineraries can do better than sorting itineraries by price.

This work threw us into the tricky domain of evaluating supervised machine learning models from a cost/benefit perspective. What sort of offline evaluation improvement warrants running an online experiment? Is an improvement of x% in precision worth the work (and time) that it will take to run an A/B test? What is “wrong” with this process if many models with better offline scores don’t perform better in online experiments? These are problems that I’ve mentioned in a previous post; to date, I still don’t think that there are any definitive answers. When developing a model offline, we need to be able to measure its performance with particular metrics (like precision); however, the actual user behaviour that the model aims to support is often not captured by the same metrics. Similarly, online (A/B) testing everything is infeasible— the best way we have to prioritise what to test next, in supervised learning, is to run offline evaluations and then discuss their results with other stakeholders.

Lesson: This highlights the importance of considering the big picture and debating the pros and cons of running a specific machine learning experiment with various stakeholders. Accuracy is not enough!

3.

The itineraries mentioned above are only one part of the app’s search experience; indeed, the app’s search result interface is going beyond itineraries and towards being designed around the idea of widgets. For example, this tweet shows a screen shot of the app giving users suggestions to change their search dates.

An interesting problem that emerged from this is how to design the “best” layout for a given user’s search when various widgets are available. As I described in the keynote I gave at the 2017 AI Tech World conference (slides here), the main approach that we were exploring is the use of multi-armed bandits to learn to create layouts for different searches. Although this was the first time that I had worked with multi-armed bandits, I felt confident that the research literature and resources available online about this approach would be there to inform each step we needed to take. I was wrong!

One of the fascinating aspects of this work was that there are many practical decisions that needed to be made (e.g., what variability in user experience should be allowed) that are often taken for granted or altogether ignored in the research literature.

Lesson: the devil is in the detail. While machine learning does provide useful abstractions, there are many practical decisions that need to be made in a product that is driven by machine learning that govern how it works.

2.

I’ve seen the “data science is 80% data cleaning” phrase in all different shapes and sizes. It often comes up at Data Science meetups and conferences. However, one topic that I feel isn’t discussed as much as it should be is about working, as a Data Scientist, within and across multi-disciplinary teams.

A recurring conversation that I had with engineers, product managers, and designers started with: what is machine learning? Venturing into this hyped and alchemist-filled field can be both daunting and overwhelming — and it is unclear how to get the best result when intersecting with other discipline’s methods. How should data scientists factor in qualitative research results into their workflow? How does machine learning fit into experience design?

Naturally, a lot of practical questions emerge that do not have much to do with machine learning itself, but about how to understand and make use of the benefits that this tool could provide. My main take-away was yet another 80/20 rule: data science is 80% education and 20% implementation.

I mean this as a two-way street: I learned a lot by having regular 1–1s with product owners to understand how they do things: for example, here’s a great post by Andrea Sipos on the development of one of the app’s features. Similarly, I spent time trying to communicate how machine learning works and fits into this picture. After a few of these conversations, I wrote a blog post on machine learning for product managers; here’s a similar post by Fabien Girardin that discusses the implications of machine learning for designers.

1.

There’s a great post by Monica Rogati that discusses the “AI hierarchy of needs;” the foundations that a company needs to build before it can reach the peak of advanced machine learning in production. The post describes how you need to be able to crawl (collect, load, move, transform data) before you can walk (experimentation, simple machine learning), and walk before you can run (use state of the art machine learning).

The projects that I’ve described above all started and progressed to different stages of this hierarchy. However, just as software is never finished, it’s very challenging to claim that you are “finished” with the one part of the AI journey and will move up the hierarchy to the next step.

In other words, you won’t stop caring about being able to crawl well (count, load, transform data) when you have started caring about walking (experimentation). As I described in this twitter thread, building app features that use machine learning relied on standing on the shoulders of giants — for example, the other teams that develop the infrastructure and experimentation services.

Wrapping Up 🌍

When I joined Skyscanner, I was the first data scientist based in the London office, at WeWork in Moorgate. Since I joined, Skyscanner was acquired by CTrip, it acquired Twizoo, and Trip.com joined forces with Skyscanner. Skyscanner moved into new offices near Tottenham Court Road, and there are now 5 London-based data scientists, more than 20 across all of the Skyscanner offices, and the team is continuing to grow.

Naturally, the projects I’ve mentioned above are a very thin slice of the various places where data scientists at Skyscanner are working. In April 2017, we organised and hosted a series of public lightning talks as part of the London Data Science Festival that gave a glimpse into some other projects. At this event, Dima Karamshuk gave a talk on optimising content caching (here), Ruth Garcia gave a talk on evaluating ad quality (here), and Ryszard T. Kaleta gave a talk about machine learning with social data (here).

Suffice to say, if you follow Skyscanner Engineering you’re likely to run into more data science blog posts in the near future. For example, here’s a recent one from Sri² about multi-touch attribution.

Do you have any thoughts or want to share your own insights? Feel free to reach out to on twitter.

Thanks:

- Ewan Nicholson,

- Sri² Perangur,

- Dima Karamshuk,

- Ruth Garcia

- Andrea Sipos

for the feedback on this post, and for being generally awesome people.