Crowdsourcing in the London underground with wifi data

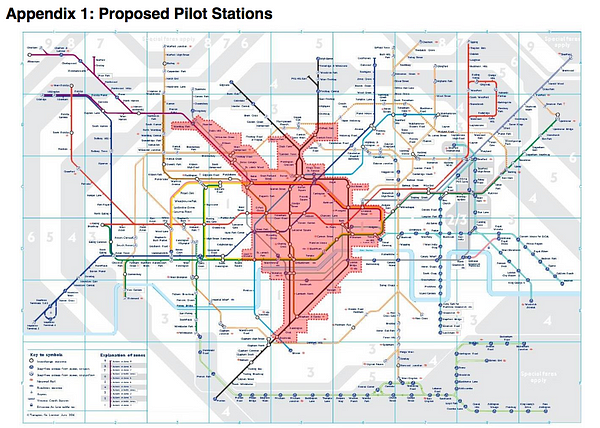

In November 2016, Transport for London (TfL) announced a 4-week trial where they would collect wifi connection data “in order to better understand how London Underground passengers move through stations and interchange between lines.”

TfL discusses some of the details of the trial in this freedom of information request. In particular:

The WiFi pilot is an internal initiative and has been developed by an in-house TfL team using our existing infrastructure. For the pilot we developed our own method and software for collecting data from our the access points. We store the pseudonymised and encrypted MAC addresses, the date and time of the connection, the device connection status and the individual access point they connected to, and therefore the London Underground station and location within a station where the device connected.

Previous Experiments with Tube Crowds

Seeing TfL undertake this experiment is exciting, and probably a big step forward for the research field of urban computing. A number of years ago, when I was a postdoctoral researcher at UCL, I had been working on a project that was trying to do the same thing — using smartphones.

The project started out with a focus on the Oyster card data. The most recurring frustration we had, when analysing the troves of data that TfL collects via its smartcard, was that we only saw entries/exits — and nothing in between. Was the trip good? Slow? Crowded? Disrupted? We could never really know.

We therefore decided to run a small experiment where we would ask participants to crowd source that information for us. We started building an Android app. After a number of iterations, we settled on a simple interaction: passengers could rate the current tube line they were on, and leave an optional message about the experience they were having. I presented the slides on the left at a conference where we reported the results of the trial.

A thematic analysis of the data we received uncovered some cute results: (1) passengers reported on a variety of topics, ranging from temperature to seat availability, (2) the ratings that passengers gave were, on the whole, mostly positive, and (3) there were a few instances where the crowdsourced reports were more timely than disruptions announced via the official TfL update feeds.

From Crowdsourced Reports to Wifi Data

The biggest problem with the first Tube Star study, though, was the small amount of data that we received. Getting an app into the hands of thousands of London tube passengers was a challenge that we simply did not have the resources to face, and was seen as the major limitation to any future public transport service that would rely on crowdsourced data.

By this time, however, I had moved on to a new project that had a more distinct focus on smartphone sensors. As I learned about how to efficiently collect data from various sensors, I realised that wifi scans could be matched with known hotspot locations, and that this could be used to passively track passengers who were in the London Underground.

My first step was to send a freedom of information request to TfL: I asked them to provide me with the locations and ids of all their wifi hotspots. With those in hand, I would have been able to automatically identify which station a user was in, given the wifi hotspots surrounding them. TfL did not release the ids I needed — citing security concerns: “In this instance the exemption has been applied as disclosure of the information requested would be likely to adversely affect the safety and security of TfL employees and members of the general public.”

I decided to go ahead anyway. I updated the Tube Star app (and the ethical approval that it had originally received) to also collect filtered wifi traces: when Android phones with the app installed would scan for wifi connectivity, they would keep a record of any Virgin Media WiFi that they came across. I got around the missing data that matched hotspot ids to stations by going back to crowdsourcing. If a hotspot did not match any tube station known to my app, the app would ping the user and directly ask “‘where are you?” and allow them to select a station. I re-released the app, and watched the data start flowing in.

The full results of this 2nd study have not been published to date; however, I did present them in a variety of conferences, including a workshop in 2015 that TfL hosted in its offices near Victoria.

Case 1 in the slides on the left (slides 11–30) give an overview of these results. With only 34 users who updated and consented to the new data collection, the app collected over 100,000 wifi scans that matched the London Underground.

I presented these results as a contrast between what the Oyster card tells us (entry and exit), what journey planning tools tell us should happen in between, and what we actually observe with wifi traces. There were some interesting highlights. For example, just 2% of the connection sequences that started at Pimlico and later appeared at Victoria had Green Park as an intermediary — the wrong direction of travel.

The TfL trial results & future advertising

The recent TfL trial was slightly different from this previous research — they collected data from the hotspot devices themselves, rather than relying on passengers to install data-collecting apps. Gizmodo recently published a piece covering TfL’s trial, using data obtained via a freedom of information request. I was thrilled to see that many of the behaviours that they have observed are in line with the smaller data that I collected with Tube Star. Their results are also likely to have much higher coverage and granularity than the study that I ran.

However, one item that the piece focuses on is that this data could be used “[…] to inform advertising decisions on the Tube network”. While research by @danielequercia & co (“Ads & the City: Considering Geographic Distance Goes a Long Way”) shows that, indeed, “ knowing the kind of people who are willing to go to, say, certain restaurants or bars […] translates into low-cost marketing strategies for bars and restaurants that are willing to attract new crowds ,” it is always a bit underwhelming to announce the creation of a new dataset that has huge potential, and then say that it will be used for advertising.

Alternative uses of TfL wifi data

While the TfL documents clearly show that they are going to use this data for analytic purposes (to help them understand how customers use the network), there are definitely future applications for this data that go beyond advertising — if they can not only collect the data, but also start building services that use it. What about…?

- Timely & relevant alerting. If TfL knew I was 2 stops away from making a potential route choice, could it tell me which route is busier, and even perhaps nudge me to go one way or another (like the game for the underground chromaroma did)? If TfL knows the routes that I regularly take, they’re likely to be able to predict when and where I travel. Could they use this to notify me about relevant disruptions, both planned and unplanned? Could TfL overcome all of the limitations that I had with the 1st Tube Star study, and also collect crowd-sourced passenger updates?

- Accessibility & station design. Could TfL harness wifi detection and localisation to improve accessibility, like they are doing with the wayfindr project? If they can detect crowding, could they use that to redesign stations to cater for easier walk-through routes?

- (No More) Penalty fares. Right now, if you don’t touch out, you may be subject to a penalty fare for an incomplete journey — and we regularly hear the reminder about touching in and out. If TfL has tracked my phone, couldn’t they figure out where I forgot to touch out?

- Better research into passengers’ experiences. If TfL can link phones, smartcards, and passenger surveys, and give that data to its academic partners, they would enable an entirely new field of research that has been inaccessible to date. Here is an example where we only had two linked sources (Oyster cards and survey results).

Maybe, one day, our phones will even replace the Oyster card altogether — doing away the need for gates at stations. In the mean time, I’m looking forward to seeing more results from this trial emerge, and for new and interesting ideas of how this data can be put to great use.