Intuition in machine learning

I’ve just finished Week 5 of the Coursera/Stanford Machine Learning course. It has been a mixture of refreshing, relearning, and new for me. I had already been using, building, and researching/evaluating machine learning algorithms for a number of years. I therefore felt like I ‘knew’ a lot of the concepts, particularly the introductory ones. I put ‘knew’ in quotes, however, since I’ve always had a feeling that I don’t know them well enough, no matter how many times I’ve used them.

It has therefore been particularly refreshing to hear Andrew Ng recognize that the inner workings of ML algorithms often don’t make intuitive sense. At the end of this week’s lecture videos, he talks about how, although he has been using neural networks for years (indeed, he is behind some of the biggest breakthrough technologies in this domain!), he sometimes feels he doesn’t quite grasp how they work.

What struck me when going through this course, though, is that there doesn’t seem to be a single way to learn machine learning concepts— we create an intuitive understanding of algorithms by approaching them from different perspectives. I’ve put an example with four perspectives below. All of these approaches are used in the Coursera course, so why do feelings of inadequacy remain?

Example: gradient descent

Here are four perspectives of the same concept, and some reasons why each of them is incomplete.

Perspective #1: Motivations

You have an ML algorithm that has certain parameters. You don’t know what those parameter values should be, and would like to learn them. What you do know is how costly (or how much error happens when) using certain values. The goal of gradient descent is to find the set of parameter values that minimise your cost function. To do that, gradient descent starts at an initial value, and then ‘steps’ the parameters towards values that reduce the cost. It keeps doing that until the improvement in those steps is very small.

Pros: this perspective is a great place to start. It gives you a high-level view of what is supposed to happen. It allows you to see beyond the ML algorithm itself, and think about what you are trying to achieve.

Cons: this perspective does not actually give us enough information to use this method. Furthermore, the high-level way that we talk about a problem constrains us to think about that problem in a particular way. For example, recommender system design is constrained by the way we think about it, as a system of ‘users’ and ‘items’ (this metaphor does not fit many practical applications where we want to build a personalised system).

Rating: essential, but insufficient.

Perspective #2: Math and Equations

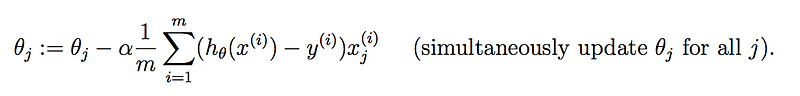

Here is the update rule for gradient descent (Credit: Week 1 coursework, Coursera/Stanford Machine Learning):

Pros: At its heart, machine learning is about understanding various mathematical concepts: from simple things like addition and multiplication to linear algebra, optimisation, and matrix operations. This is the ‘meat’ of the algorithm.

Cons: If you’ve been away from these concepts for some time, then diving straight into machine learning from this perspective is not ideal. There are differences in how researchers write these equations and you need to be fully versed in the notation. For example, the snippet above uses h(x) to denote a regression model’s prediction, which I have often seen as \hat{y}. If you come from a Computer Science/programming background, some pseudocode may be much easier to read than an equation.

Rating: important in theory, often difficult/inaccessible in practice.

Perspective #3: Pictures

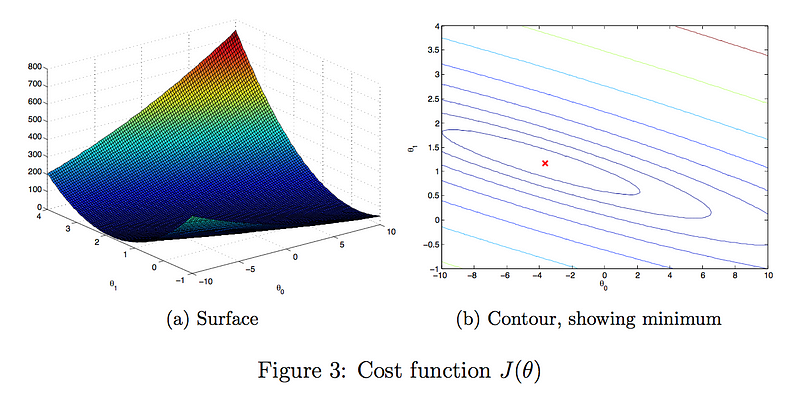

Here is what you get if you plot a simple linear regression’s parameters vs. the cost, as a surface plot (left) and contour plot (right). The goal of gradient descent is to get to the lowest vertical point in the surface plot (Credit: Week 1 coursework, Coursera/Stanford Machine Learning).

Pros: visualisations are the quickest way to grasp a simple concept. It is immediately clear where the ‘lowest’ point of the surface plot is. For non-convex problems, a similar plot will immediately show that there are multiple ‘low’ points, so understanding local minima is very easy as well.

Cons: Visualisation does not scale to high-dimensional problems, so it is limited to toy/practice scenarios.

Rating: good for simple concepts and educational examples, otherwise usually unsuitable.

Perspective #4: Code and Practice

If putting machine learning theory into practice is your goal, you cannot get away from code. Here is how you fit a simple linear model in scikit-learn, which is what all of the work on gradient descent was leading up to.

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

predictions = model.predict(X_test)

Pros: A lot of imperative programming languages are very different from learning about the ‘maths’ of ML, or knowing how things work in theory. My confidence in ‘knowing’ how a particular algorithm works is usually proportional to how much of it I could implement from scratch. Reading others’ code is a great way to understand, step-by-step, what is happening under the hood.

Cons: There are actually quite a few here.

- The Coursera/Stanford course uses Octave, which I have not had any reason to use before (and I do not know why I would use it again). I would imagine that it would take quite a bit of potentially duplicated work to design algorithms with Octave and then move them into production in some other language.

- The scikit-learn example above has not taught us anything: many machine learning packages are becoming so good that you don’t need to be a mechanic to drive the car anymore.

- When it comes to kaggle competitions, it is not practical to both implement algorithms from scratch (to learn) as well as actually compete (to perform)— so competing feels like more of an exercise in feature engineering and parameter tuning.

Rating: essential in practice, but there is a trade-off between coding to learn and coding to build a useful system.

Conclusion: keep (re-)learning

All of the work that I’ve done that has used machine learning started during my PhD, so there while there are some concepts I have never used (e.g., backpropagation, this week’s Coursera topic) I realized that I have never formally been taught any of them — I learned by doing. It’s been great to re-learn so many things from different perspectives, and pay more attention to the details that I typically would overlook.

Quora has recently hosted a number of sessions with well-known machine learning (ML) researchers and practicioners. One of the questions that they all got was: “How should you start a career in Machine Learning?” Xavier (who is a great mentor, colleague, and friend!), Andrew, and Ralf all provided interesting insights, that range from the theory to the practice of machine learning.

They suggest learning about querying large datasets, linear algebra, optimization, code/software engineering, and using online courses and machine learning competitions to hone your skills. While there are differences in the details of what they suggest, there is one common theme: learning about machine learning does not end.